Creation of the Federal Reserve System

Date: 1913-12-23 AD

The creation of the Federal Reserve System on December 23, 1913, established the central banking authority of the United States. It was enacted through the Federal Reserve Act, signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, in response to recurring financial panics, banking instability, and the absence of a coordinated monetary policy mechanism in the U.S. economy.

The immediate catalyst for the Federal Reserve was the Panic of 1907, a severe financial crisis marked by bank runs, stock market collapses, and liquidity shortages. During the crisis, private financier J.P. Morgan coordinated emergency interventions among banks to stabilize the system, exposing the reliance on individual actors rather than formal institutions. This event convinced lawmakers and business leaders that a centralized monetary authority was necessary.

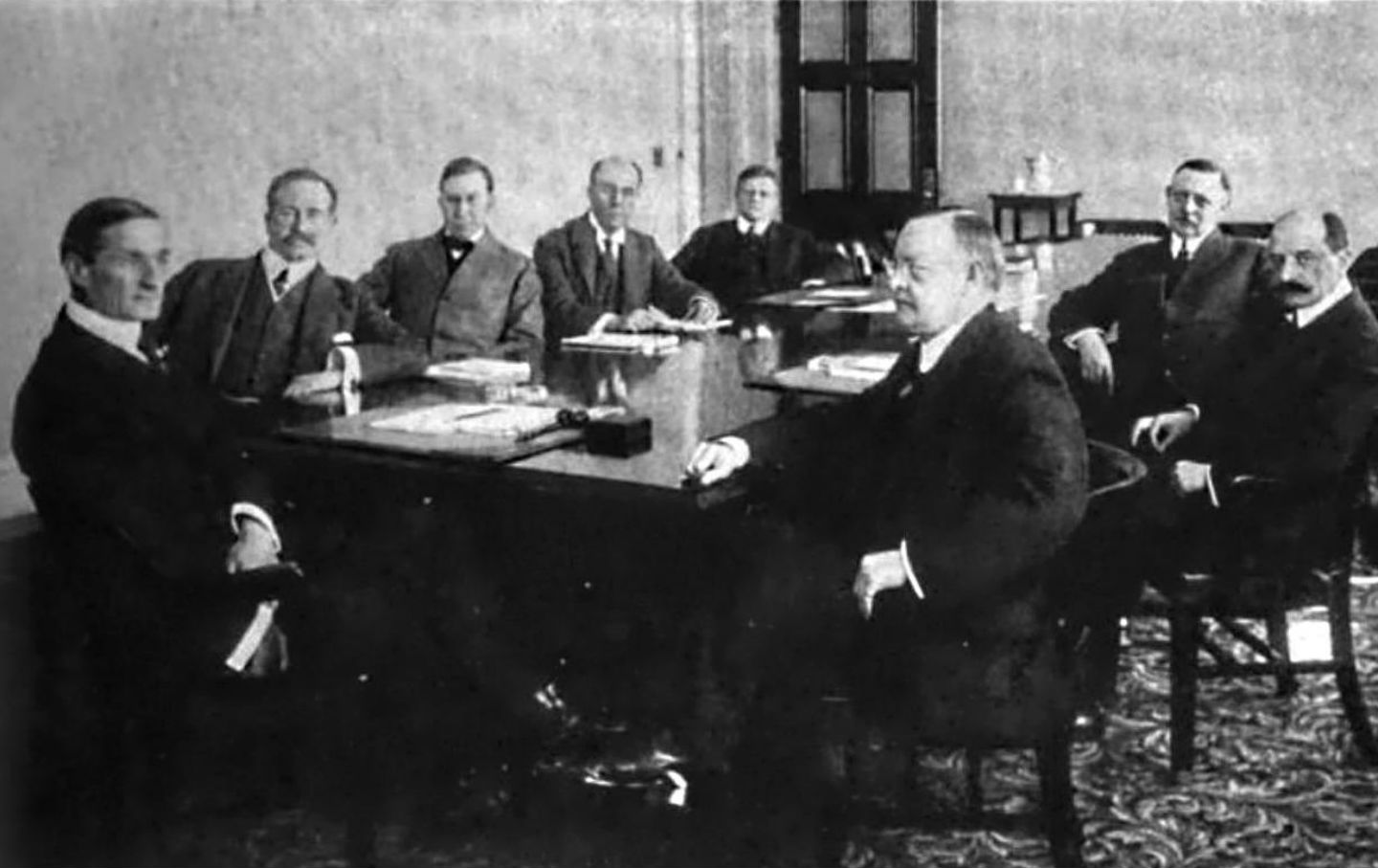

In response, Congress created the National Monetary Commission in 1908, chaired by Senator Nelson W. Aldrich. Aldrich and other commission members studied European central banking systems, including the Bank of England and the German Reichsbank. In 1910, Aldrich convened a secret meeting at Jekyll Island, Georgia, involving key figures such as Paul Warburg (Kuhn, Loeb & Co.), Henry P. Davison (J.P. Morgan & Co.), Frank Vanderlip (National City Bank), and Benjamin Strong. The group drafted a framework for a central banking system that balanced private banking interests with public oversight.

The final legislation reflected political compromise. Progressive Democrats, led by President Wilson and Congressman Carter Glass, rejected a fully private central bank and instead designed a hybrid system. The Federal Reserve System consisted of a central governing body, the Federal Reserve Board (later the Board of Governors), and twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, distributing power geographically. The system was placed under federal oversight, while member banks were required to hold shares in their regional Federal Reserve Banks.

The Federal Reserve was granted authority to issue a centralized currency (Federal Reserve Notes), act as a lender of last resort, regulate member banks, and manage monetary policy through tools such as discount rates and reserve requirements. Over time, its responsibilities expanded to include open market operations, financial supervision, and systemic risk monitoring. The Federal Reserve operates independently within government, meaning its decisions are insulated from direct political control but subject to congressional oversight.

The establishment of the Federal Reserve reshaped U.S. financial governance, reduced the frequency of banking panics, and integrated the United States more deeply into global financial systems. It also linked monetary policy to international markets, foreign central banks, and institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank in later decades.

The creation of the Federal Reserve System on December 23, 1913, established the central banking authority of the United States. It was enacted through the Federal Reserve Act, signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, in response to recurring financial panics, banking instability, and the absence of a coordinated monetary policy mechanism in the U.S. economy.

The immediate catalyst for the Federal Reserve was the Panic of 1907, a severe financial crisis marked by bank runs, stock market collapses, and liquidity shortages. During the crisis, private financier J.P. Morgan coordinated emergency interventions among banks to stabilize the system, exposing the reliance on individual actors rather than formal institutions. This event convinced lawmakers and business leaders that a centralized monetary authority was necessary.

In response, Congress created the National Monetary Commission in 1908, chaired by Senator Nelson W. Aldrich. Aldrich and other commission members studied European central banking systems, including the Bank of England and the German Reichsbank. In 1910, Aldrich convened a secret meeting at Jekyll Island, Georgia, involving key figures such as Paul Warburg (Kuhn, Loeb & Co.), Henry P. Davison (J.P. Morgan & Co.), Frank Vanderlip (National City Bank), and Benjamin Strong. The group drafted a framework for a central banking system that balanced private banking interests with public oversight.

The final legislation reflected political compromise. Progressive Democrats, led by President Wilson and Congressman Carter Glass, rejected a fully private central bank and instead designed a hybrid system. The Federal Reserve System consisted of a central governing body, the Federal Reserve Board (later the Board of Governors), and twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, distributing power geographically. The system was placed under federal oversight, while member banks were required to hold shares in their regional Federal Reserve Banks.

The Federal Reserve was granted authority to issue a centralized currency (Federal Reserve Notes), act as a lender of last resort, regulate member banks, and manage monetary policy through tools such as discount rates and reserve requirements. Over time, its responsibilities expanded to include open market operations, financial supervision, and systemic risk monitoring. The Federal Reserve operates independently within government, meaning its decisions are insulated from direct political control but subject to congressional oversight.

Beneficiaries: The creation of the Federal Reserve was designed to stabilize the U.S. financial system, but benefits were uneven. Member banks received access to emergency liquidity and reduced risk of bankruptcy. Large financial institutions and Wall Street gained influence over credit and monetary policy, while business and industrial leaders benefited from more predictable access to loans. The general public benefited indirectly through long-term economic stability and reduced banking panics, and governments gained tools for managing the economy. However, smaller banks and rural communities initially had limited direct access, and some critics argue the system concentrated financial power among elites.

Note: While myths have circulated linking the Titanic to Federal Reserve founders, the planners of the Fed—such as Paul Warburg, J.P. Morgan, and Nelson Aldrich—were not aboard. J.P. Morgan had booked passage but canceled, avoiding the disaster. Other wealthy businessmen did perish, contributing to the myth.

The establishment of the Federal Reserve reshaped U.S. financial governance, reduced the frequency of banking panics, and integrated the United States more deeply into global financial systems. It also linked monetary policy to international markets, foreign central banks, and institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank in later decades.

The creation of the Federal Reserve System on December 23, 1913, established the central banking authority of the United States. It was enacted through the Federal Reserve Act, signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, in response to recurring financial panics, banking instability, and the absence of a coordinated monetary policy mechanism in the U.S. economy.

The immediate catalyst for the Federal Reserve was the Panic of 1907, a severe financial crisis marked by bank runs, stock market collapses, and liquidity shortages. During the crisis, private financier J.P. Morgan coordinated emergency interventions among banks to stabilize the system, exposing the reliance on individual actors rather than formal institutions. This event convinced lawmakers and business leaders that a centralized monetary authority was necessary.

In response, Congress created the National Monetary Commission in 1908, chaired by Senator Nelson W. Aldrich. Aldrich and other commission members studied European central banking systems, including the Bank of England and the German Reichsbank. In 1910, Aldrich convened a secret meeting at Jekyll Island, Georgia, involving key figures such as Paul Warburg (Kuhn, Loeb & Co.), Henry P. Davison (J.P. Morgan & Co.), Frank Vanderlip (National City Bank), and Benjamin Strong. The group drafted a framework for a central banking system that balanced private banking interests with public oversight.

The final legislation reflected political compromise. Progressive Democrats, led by President Wilson and Congressman Carter Glass, rejected a fully private central bank and instead designed a hybrid system. The Federal Reserve System consisted of a central governing body, the Federal Reserve Board (later the Board of Governors), and twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, distributing power geographically. The system was placed under federal oversight, while member banks were required to hold shares in their regional Federal Reserve Banks.

The Federal Reserve was granted authority to issue a centralized currency (Federal Reserve Notes), act as a lender of last resort, regulate member banks, and manage monetary policy through tools such as discount rates and reserve requirements. Over time, its responsibilities expanded to include open market operations, financial supervision, and systemic risk monitoring. The Federal Reserve operates independently within government, meaning its decisions are insulated from direct political control but subject to congressional oversight.

Beneficiaries: The creation of the Federal Reserve was designed to stabilize the U.S. financial system, but benefits were uneven. Member banks received access to emergency liquidity and reduced risk of bankruptcy. Large financial institutions and Wall Street gained influence over credit and monetary policy, while business and industrial leaders benefited from more predictable access to loans. The general public benefited indirectly through long-term economic stability and reduced banking panics, and governments gained tools for managing the economy. However, smaller banks and rural communities initially had limited direct access, and some critics argue the system concentrated financial power among elites.

Note: While myths have circulated linking the Titanic to Federal Reserve founders, the planners of the Fed—such as Paul Warburg, J.P. Morgan, and Nelson Aldrich—were not aboard. J.P. Morgan had booked passage but canceled, avoiding the disaster. Other wealthy businessmen did perish, contributing to the myth.

The establishment of the Federal Reserve reshaped U.S. financial governance, reduced the frequency of banking panics, and integrated the United States more deeply into global financial systems. It also linked monetary policy to international markets, foreign central banks, and institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank in later decades.

Note: While myths have circulated linking the Titanic to Federal Reserve founders, the planners of the Fed—such as Paul Warburg, J.P. Morgan, and Nelson Aldrich—were not aboard. J.P. Morgan had booked passage but canceled, avoiding the disaster. Other wealthy businessmen did perish, contributing to the myth.